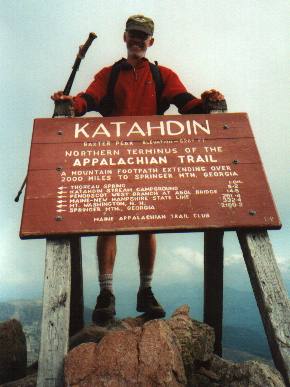

Katahdin

Mile 2168

Why I Hiked, and how You can Successfully Through-Hike the Trail

My name is Bruce Nelson. I was a career smokejumper out of Fairbanks, Alaska. My close friends often call me Buck. During my summer on The Trail however, I was known by my trail name of “Colter.”

There are many reasons to hike the Appalachian Trail, and many ways to do your hiking. Most folks are out to enjoy a section hike, a few hours or days of exploring a favorite stretch of trail. Some choose to hike the entire trail in one calendar year; this is called a “thru-hike.” A thru-hike normally takes from 4-7 months and winds along the 2,168 miles and 14 states the trail passes through.

In the fall of 2000, I’d been fighting wildfires for many years. I realized that it was time for me to take a summer off to recharge my batteries and to enjoy some of the adventures I’d been dreaming about. In August of 2000 I left for six weeks alone in the Alaska wilderness (see my video page.)

During a fall and winter of travel, writing and planning, I decided that I’d attempt a thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail. A thru-hike would offer me several things I was looking for; a grand adventure, a physical challenge, travel in new places, a summer in the outdoors, and a chance to meet new people.

After a great deal of research and preparation, I selected my equipment. I’m a lightweight backpacker at heart, and going lightweight seemed to make even more sense on such an epic hike, where staying fit physically and mentally was so important.

Through www.trailplace.com I contacted a “trail angel” in Atlanta who offered to bring me to the trailhead on March 31. Chuck proved to be fine fellow and housed my first trail friends, Stan and Tina, the night before we headed out to the trail.

Around noon the next day, we stood atop Springer Mountain, then turned and headed towards Maine. It was hard not to feel like a fraud when boyscouts would stand in awe after finding out we were walking all the way to Maine. I thought it was interesting that people seemed just as impressed when I was PLANNING to hike the whole way as when I had completed to trail.

People who enjoy the experience as a whole are the ones who notice the magic more than the discomfort and boredom. Which type of person will you be? One thing to consider is how much backpacking and camping experience you have. The more time you’ve spent outdoors under arduous conditions, the better of an idea you’ll have of how you’ll react to the realities of the trail. Here’s a question I like to ask people: “What do you really enjoy doing? Golfing? OK, how would you feel about golfing all summer, rain or shine, every day, all day?”

If you think I’m overstating the negatives, consider that 25% or less of the people who commit to a thru-hike, actually finish. I think it’s fair to say that most people who don’t finish have the ability to finish the trail if they truly had to, but they find it isn’t worth the cost in physical or mental discomfort. Vast numbers of hikers find they get too homesick, discouraged or disillusioned. Many have the mental drive but suffer injuries that preclude their finishing. Somewhere in the neighborhood of 25% drop out by Neal’s Gap, only 30 miles from the start of the trail. There’s nothing shameful about not finishing the trail, of course, but it’s wise to look at the endeavor realistically before you begin. Remember, it’s not primarily a CAMPING trip, it’s primarily a HIKING trip.

- The greatest is an unshakable dedication to completing a thru-hike

- Confidence in, and knowledge of, themselves,

- The ability to maintain good morale in tough conditions,

- Decent physical condition, no major problems with knees, ankles, backs, feet or hips,

- Good judgment: knowing when to push and when to rest, etc.

- Outdoor experience

- It was a lot STEEPER that I thought it would be. According to Wingfoot, there are about 91 vertical MILES of climbing and descents on the AT. I’m sure it’s that much, at least! 91 vertical miles of climbing is 480,480 vertical feet. If you finish your hike in 5 months, or lets call it 150 days, that’s 3,203 feet of climbing and descent EVERY day. The trail was so steep and slippery in some places in New England that it was hard for me to believe that it was the AT. Of course, there were hundreds of miles of mellow trail too, and it doesn’t take a mountain climber to do the AT.

- Woodticks were a bigger factor than I expected. I grew up around woodticks without suffering any ill consequences, but during the summer of 2001 I TWICE had to take antibiotics to fight woodtick infections. I talked to several folks who had contracted Lyme disease, that summer or before.

- It was easier to get food and supplies than I thought. Seldom did I have to carry more than four days worth of food.

- There were a lot fewer single ladies on the AT than I expected. This was a favorite topic of my buddy Metro!

- People were so friendly. I had no problems with locals. Usually it was easy to hitch to and from town, and many times trail angels left cold drinks and food at trail crossings.

- Virginia is not flat, contrary to what you might hear.

- I rarely slept in shelters. For me, shelters tended to be mousy, buggy, loud and had hard floors. I think what appeals to people most is the social aspect of the shelter, and the avoidance of putting up and taking down their tents/tarps, especially when it’s rainy. With the right folks, shelters were great, but I usually prefered tarping out, often in the company of friends.

The more you want to pick up “snail mail,” special food items, or other items from home such as prescriptions, the more mail/food drops you’ll want. The advantages of mail drops are obvious; it’s fun to get packages and mail from friends and relatives. You can also get food items that may be hard to find on the road, and may be able to get them cheaper. For me though, the disadvantages outweighed the advantages in almost every case:

- To me, the trail is largely about freedom. Mail drops tend to make you speed up or slow down so you arrive at the right place at the right time.

- Before you start your hike, you don’t know which foods you’ll get tired of. Also, MOST folks who buy a summer’s worth of backpacking food end up not completing their hike.

- Often a food drop is missed, and there’s lots of hassles for everyone involved to get the package to where you’ll be next.

- There’s a certain burden placed on your support crew back home.

- Mailing food has grown more expensive. Saving on your grocery bill is usually not a sufficient reason to do a food drop.

- Usually you have food left when you get your food drop, forcing you to give away, throw out, or carry the extra.

If I were going to hike the AT again, I wouldn’t plan ANY food drops. A thru-hike requires flexibility. Here’s a list of common food drop towns.

- Spend several weeks getting in good shape before the hike. Ease your way into it by starting out with a very light load on flat ground, and increasing the length, steepness, and weight as you progress.

- Don’t push too hard during the first days of your hike. Above all, don’t hurt yourself! I saw people get crippling blisters right off the bat. PREVENT blisters. Wear shoes that fit and stop and treat hotspots before blisters develop. Take a couple hours before you even buy your footwear and read through the articles on Fixing Your Feet especially the pages on blister prevention and footwear fit.

- As you get in shape, increase your mileage. Get in the habit of setting goals for the day. There are lots of things that may slow you down, including weather, illness, injuries, emergencies at home, etc., so don’t “get behind the curve” or you may find it impossible to catch up before those early October snows end your trip short of Katahdin.

- No Rain, No Pain, No Maine. If you never hike thru the rain and the pain, you’re not going to see Maine. That said, hike through discomfort, but don’t continue to push when you’re doing damage to your body!

- Remember to take the time to look around you. See and appreciate the forest, scenery, wildlife and people you meet.

- Be hiking at first light to see the most animals.

- Don’t be afraid of bears. As long as you don’t sleep with your head on a pizza or something, bears pose little threat. Bears instinctively realize that humans are boss. If you use bear bells, the bears won’t kill you but other hikers will. Don’t carry bear spray unless you need it to sleep. If you’re “bearanoid” sleep in shelters until you get over it.

- Hike your own hike. Don’t be concerned if others aren’t hiking up to your standards. Being a thru-hiker doesn’t make you better than other people or the center of the universe.

- Take zero days when you need them.

- Know yourself.

- Travel light. Don’t carry what you don’t really need. A lighter load will help you avoid injury, and make your hike easier and faster.

- Treat or filter your water, wash your hands before eating, and don’t share food with dirty hands. The best peer-reviewed scientific study on the Appalachian Trail concluded: Diarrhea is the most common illness limiting long-distance hikers. Hikers should purify water routinely, avoiding using untreated surface water. The risk of gastrointestinal illness can also be reduced by maintaining personal hygiene practices and cleaning cookware.

Click here for a list of my gear and equipment and clothing recommendations.

I started out my hike in pretty good shape, quite a bit better than most folks starting the trail. On the second day I did 20 miles without much trouble. Towards the end of the trail, the folks I was hiking around had gotten much stronger, while I was in only slightly better shape. My pace, therefore, was fairly consistent throughout the hike. The first week I averaged 16 1/4 miles a day. Overall, I averaged about 17.6 miles a day, including 5 “zero days.” In central Virginia, I was averaging about 20 miles a day. My longest day was 30 miles. One of my few regrets is I never really pushed to see how many miles I could do at max. I heard of a 40, even a 50 mile day! For two weeks in the toughest parts of New Hampshire and Maine, I averaged only about 13 1/2 miles a day, which included a couple of short days. Most folks probably start out fairly slow, speed up dramatically in Virginia as they get in better shape and the terrain mellows, and then, like me, slow down when they get to that famous, beautiful, rough ground in NH and ME.

Map Man has put together a very interesting page showing AT hiking rates for each section of trail. Well worth taking a look at to see what kind of miles people are hiking in the real world.

SummitPost has a Appalachian Trail Mileage Chart which can be very useful for planning, especially for distances between given points. It lists shelters, major landmarks etc.

I finished my hike on August 3, 2001. On the mountain with me that day were Windex, Del, Mukwa, Andalia, and several other friends from the trail.

Whether you are a section hiker or thru-hiker, I wish you the best of luck. Questions or comments are welcomed below.

Don’t forget to check out my Appalachian Trail Gear List

The Best A.T. Guidebook A.T. Guide |

The Best A.T. Book AWOL on the Appalachian Trail |

The Best A.T. DVD Appalachian Impressions DVD |

My Adventure Alone Across Alaska DVD |

Adventure and exploring are things I have always been into and doing this trek sounds like something I would enjoy for many reasons. I came across this page by accident but it was very informative and I thank you for sharing your experience. I just got out of the military (12yrs) so I’m no stranger to being outdoors or “long walks” with gear on my back. My questions are more logistical than anything, they are: 1. How much food and water does one need to carry and how far apart are reliable resupply points? I’m guessing living off the land… Read more »